Most people assume “ergonomic” is subjective—comfort, preference, brand hype, and tiny feature differences. But the foundation is simpler than that. Ergonomic seating has one primary biomechanical purpose: support neutral sitting postures, where the spine stays aligned and muscular strain stays low over time.

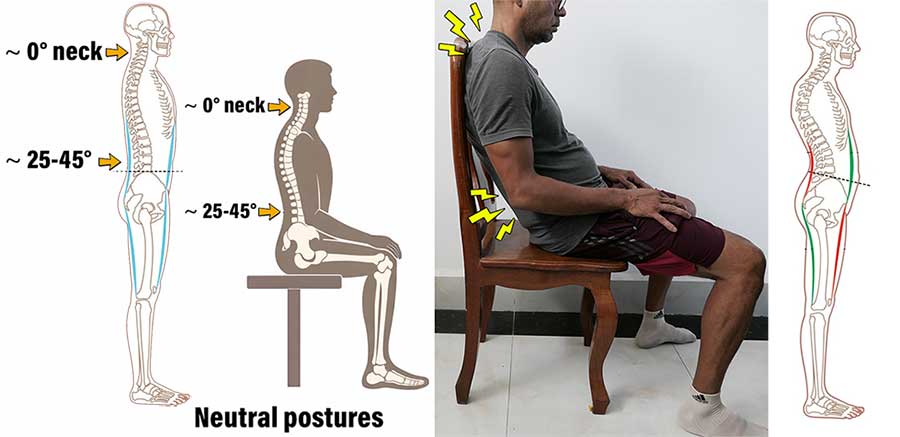

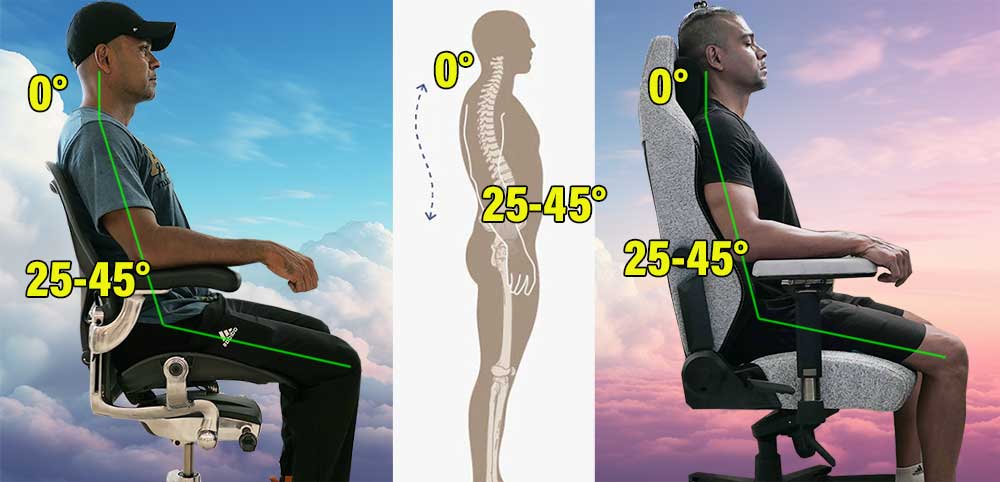

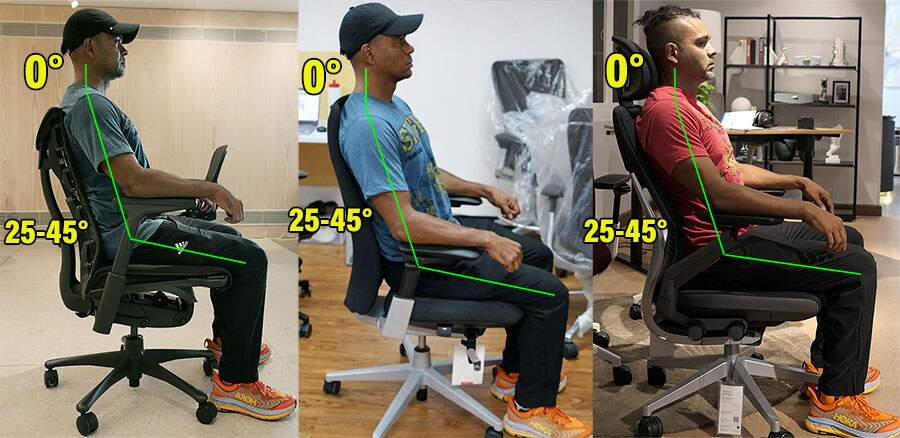

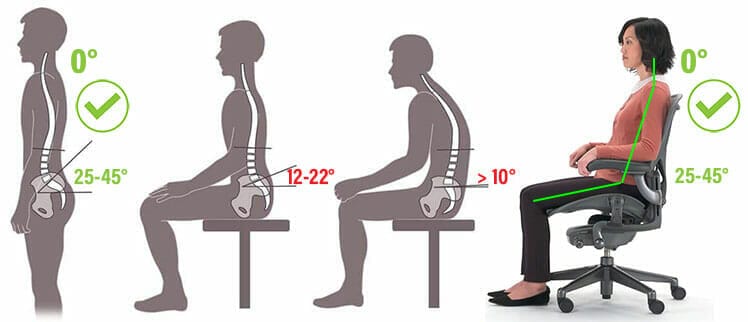

A neutral sitting posture mirrors healthy standing alignment under gravity: a balanced neck (~0° flexion) and a preserved natural lower-back curve (~25–45° of lumbar lordosis).

Chairs qualify as “ergonomic” when they provide the adjustability—lumbar support, arm support, and recline—needed to maintain this alignment.

The best part: configuring these features isn’t guesswork. There are measurable targets—like lumbar adjustments and backrest angles—that you can replicate in almost any chair.

This guide explains those targets, traces where they come from, and shows how they translate into real-world sitting styles.

Neutral Body Posture Ergonomics

These sections outline the biomechanical foundations of neutral posture and how decades of research translated it into modern seating standards:

-

Neutral Body Posture (NBP) Biomechanics:

from NASA’s zero-gravity observations to studies defining concrete biomechanical targets. -

Neutral Posture in Early Ergonomic Seating:

how neutral posture science shaped early workstation ergonomics. -

Institutional Ergonomic Standards:

how neutral biomechanics moved from research into formal guidelines. -

Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics:

how neutral benchmarks were consolidated into institutional reference texts. -

BIFMA Ergonomic Guidelines:

functional design requirements chairs must meet to support healthy sitting. -

OSHA Ergonomic Guidelines:

user-focused guidance for adjusting seating safely. -

A Practical Definition of Ergonomic Seating:

an evidence-based definition grounded in biomechanics. -

Lumbar Support Biomechanics:

learn the basics using simple, testable biomechanical benchmarks.

Shortcut: If you prefer the conclusion without a historical walkthrough, the Practical Definition of Ergonomic Seating summarizes 40 years of biomechanics and standards into a concise, evidence-based framework.

Neutral Body Posture (NBP) Biomechanics

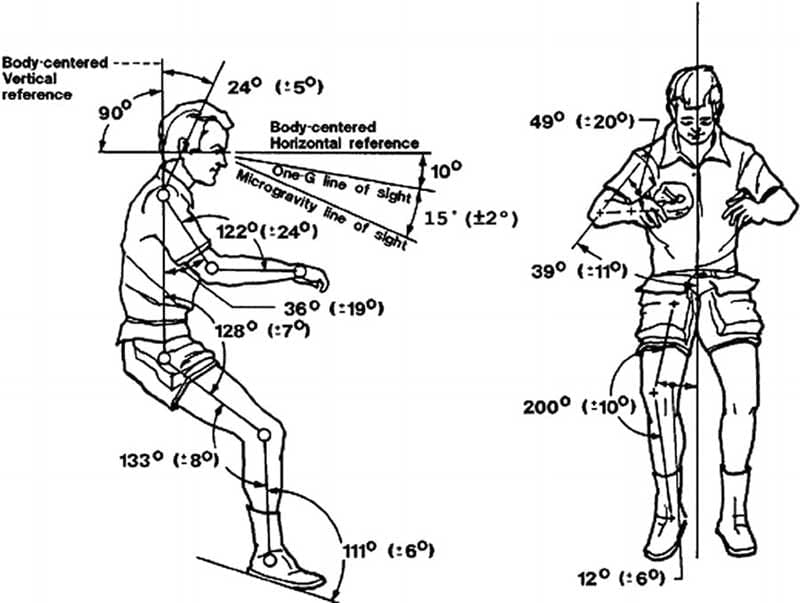

NASA first discovered the Neutral Body Posture (NBP) based on observations of astronauts in microgravity during the Skylab missions (1973–1974).

NASA / Man-Systems Integration Standards (NASA-STD-3001)(1) builds directly on Skylab findings and states that:

Key characteristics of NASA’s NBP:

- Spine: Maintains natural spinal curves; Lumbar spine remains lordotic, not flattened.

- Head & neck: Head balances naturally over the torso, with no forward flexion.

- Hips and knees: Slight flexion.

- Muscles: Minimal activation.

Subsequent ergonomic research translated this posture into gravity-bound sitting by preserving natural spinal curves, neutral head balance, and low muscular demand.

Some key findings give us a rough idea of biomechanical targets:

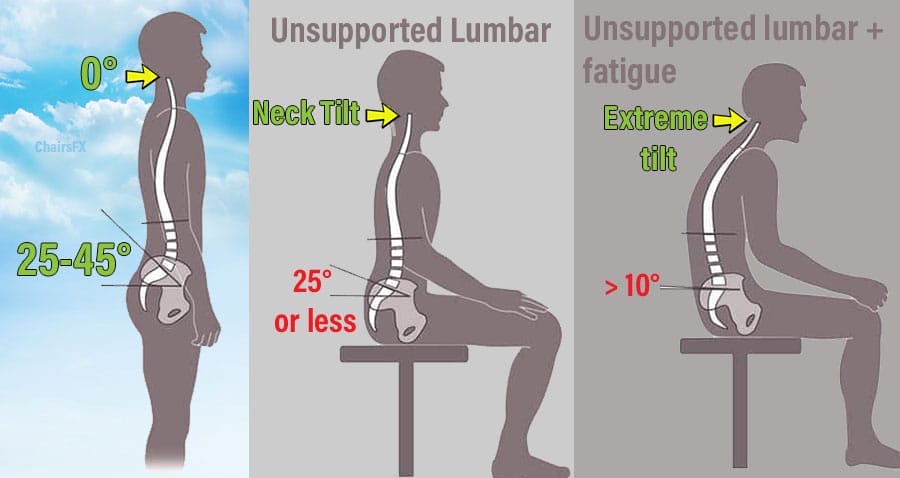

- Healthy standing posture: typically includes a lumbar lordosis (lower back curve) within a ~25–45° range(2).

- Unsupported sitting/slouching: reduces lumbar lordosis to ~20–25° or less; in many cases the curve collapses toward a near-flat alignment approaching 0°, or even lumbar flexion(3).

- Lumbar-supported upright sitting: preserves lumbar lordosis close to standing values (~45–50°)(3)

- Neck angle: Neck muscle activity remains relatively low when the head and neck are held in a neutral position (~0°–15° of flexion); increased forward flexion raises muscular load and strain. (4)

- Forward head tilt: An adult human head weighs approximately 10–12 lb. As the neck flexes forward, the effective load on the cervical spine increases(5). In a neutral (0°) posture, cervical load is ~10–12 lb; at 15° flexion it rises to ~27 lb; and at 30° flexion to ~40 lb.

Neutral Posture in Early Ergonomic Seating

In 1980, Étienne Grandjean translated NASA-era postural physiology into workstation ergonomics. His book Fitting the Task to the Man(6) became the core ergonomics reference of its era, widely used in industry, academia, and applied design—well before formal office-chair standards existed.

Étienne Grandjean, in Fitting the Task to the Man

His work explicitly rejected rigid upright sitting in favor of a posture-adaptive approach:

- Preserving lumbar lordosis

- Using recline to reduce spinal load

- Adopting task-dependent, variable postures rather than a single “correct” position

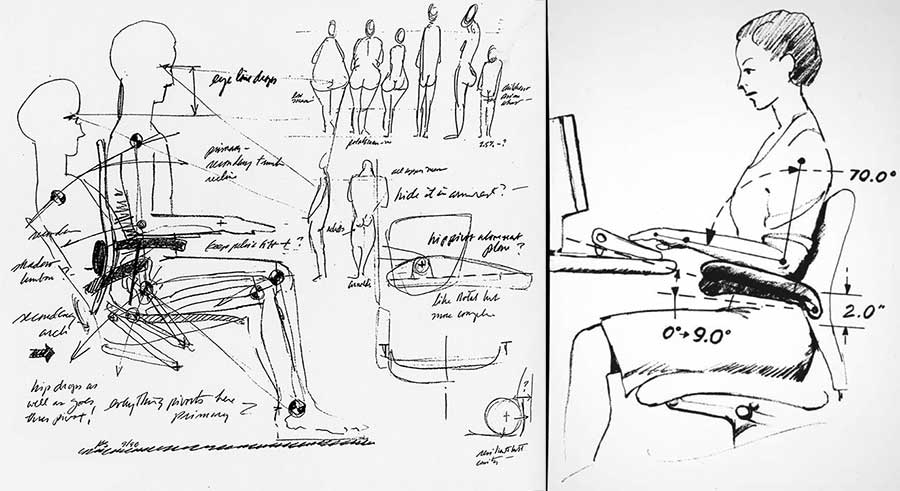

These principles shaped subsequent thinking in office seating design. In the late 1980s, Herman Miller designer Bill Stumpf—co-creator of the Aeron chair—began articulating design criteria for chairs that support a range of postures rather than a single fixed sitting position(7).

Working in collaboration with Don Chadwick, Stumpf developed prototypes that emphasized movement, recline, and continuous support rather than enforcing rigid upright alignment.

When Herman Miller released the Aeron chair in 1994, it translated the posture-adaptive philosophy into a mainstream commercial product.

It featured continuous lumbar support to preserve lordosis, a recline-biased sitting geometry to reduce spinal load, and a design intended to accommodate movement and task variation rather than enforce a single “correct” posture.

In this sense, the Aeron did not introduce new biomechanics—it was one of the first chairs to successfully operationalize established neutral-posture science at scale.

Institutional Ergonomic Standards

The 2001 paper Seeking the Optimal Posture of the Seated Lumbar Spine(3) established practical biomechanical benchmarks for neutral sitting posture:

Over the following years, this and related findings were consolidated and translated into a series of institutional ergonomic standards. This shifted neutral sitting biomechanics from research literature into applied design and workplace guidance.

Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics Guidelines

In 2005, the first edition of the Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics(8) was released. It is a compilation of institutional-level human factors and ergonomics research.

It’s intended to summarize established knowledge, in order to provide a methodological foundation for future research and applied design. The first edition illustrates how neutral biomechanics translate to seating design principles:

- Lumbar support: discussed as a means of preserving or restoring lumbar lordosis during seated tasks.

- Recline: treated primarily in terms of biomechanical load reduction (including references to reduced spinal loading at reclined angles); it also notes that recline alone does not restore lumbar lordosis without lumbar support.

- Armrests: referenced mainly in contexts such as reducing upper-limb load (e.g., wheelchair ergonomics and task support)

Over the next decade or so, these concepts crystallized further into broader guidelines, outlined below:

BIFMA Ergonomic Guidelines

In 2013, the BIFMA organization released its ergonomic guidelines for office furniture (still applicable today)(9). These guidelines define functional design requirements to accommodate healthy sitting postures.

BIFMA does not claim these settings are optimal for health. Rather, they specify the design capabilities chairs should provide so that users can adjust their seating to achieve healthy postures:

- Seat height: allows the user’s feet to rest flat on the floor or a footrest.

- Seat depth: provides sufficient clearance so the back of the knees does not contact the seat edge.

- Backrest: conforms to the natural shape of the spine.

- Lumbar support: continuous adjustable support to maintain lumbar lordosis.

- Armrests: adjustable vertically and horizontally to reduce neck, shoulder, and back strain.

BIFMA further specifies that an ergonomic chair should support a healthy range of motion, allowing users to adopt varied postures. Specifically, seating should permit backrest recline from 90° to at least 115°, while ensuring the torso-to-thigh angle does not fall below 90°.

OSHA Ergonomic Guidelines

While BIFMA provides guidelines for chair design, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) provides guidance for end users adjusting their workstations. OSHA’s chair recommendations mirror BIFMA’s design principles from a user-adjustment perspective.

OSHA’s ergonomic seating guidelines(10) emphasize three essential adjustable features:

- Backrest: should recline at least 15° from a vertical position.

- Lumbar support: should be height-adjustable to fit the lower back.

- Armrests: should be adjustable so the arms fall freely from the shoulders.

OSHA further advises users to adjust the chair in coordination with the monitor, keyboard, and desk, reinforcing that seating ergonomics must be considered as part of a complete workstation setup.

A Practical Definition of Ergonomic Seating

There is no single universal authority that defines what an “ergonomic” chair must look like. However, when the progression of ergonomic science is traced—from NASA’s Neutral Body Posture discoveries in microgravity, through applied workstation ergonomics, and into modern institutional standards—a clear, consistent definition emerges.

Across decades of research and standardization, the biomechanical goal has remained the same: support neutral body postures while minimizing muscular effort and joint loading over time.

Modern ergonomic standards from NASA, Grandjean, the Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, BIFMA, and OSHA converge on the same functional requirements. A chair qualifies as ergonomic when it provides the user with three essential adjustable components:

- Adjustable lumbar support: to preserve or restore lumbar lordosis and maintain natural spinal curves while seated.

- Adjustable armrests: to support the weight of the arms, reduce shoulder and neck loading, and help stabilize upright posture.

- A reclining backrest: to reduce spinal load, allow postural variation, and support dynamic neutral sitting rather than fixed upright alignment.

These components are not intended to force a single “correct” posture. Instead, they give users the tools to achieve and vary neutral sitting postures—characterized by preserved spinal curves, neutral head balance, and low muscular strain—across different tasks and durations.

In this sense, “ergonomic” does not describe a style of chair or a collection of luxury features. It describes a chair’s ability to support neutral biomechanics with adjustability and movement, consistent with decades of human factors research.

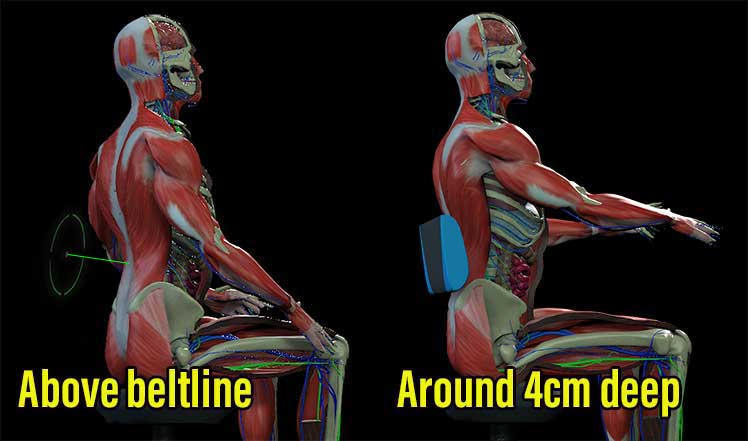

Lumbar Support Biomechanics

If a chair qualifies as “ergonomic” by offering adjustable lumbar support, armrests, and recline, lumbar support is usually the hardest element for beginners to configure correctly.

But once you understand the neutral posture endpoint, lumbar support becomes simple, objective, and testable at home:

This benchmark comes directly from seated-spine biomechanics research and explains why lumbar support works when correctly placed.

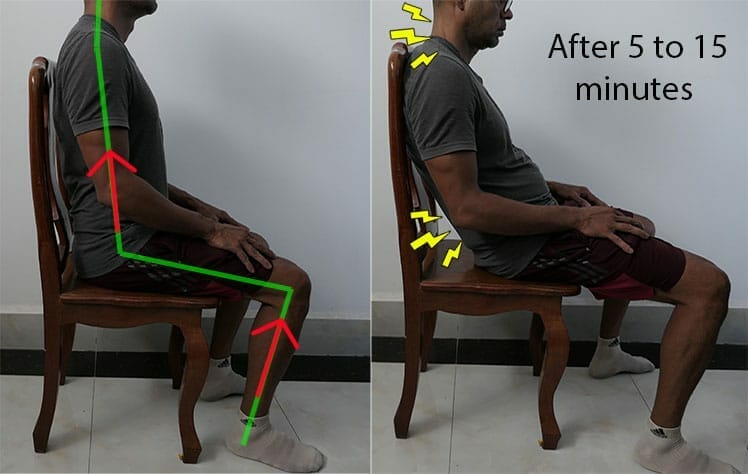

You can test this principle yourself using a basic dining chair and a rolled towel or yoga mat. First, try sitting upright without lumbar support.

Within minutes, your back muscles must actively hold posture, leading to fatigue and an increasing urge to slouch.

Then, place light pressure into your lower spine—slightly above the beltline. With even minimal support, the upper torso reflexively straightens and the neck balances more easily over the spine. Alignment improves without conscious muscular effort.

That response is the signal you’ve reached neutral alignment. To find your personal lumbar “sweet spot,” start from the benchmark:

- Position support slightly above the beltline

- Aim for gentle depth (~4 cm), not aggressive pressure

- Use recline (~100–110°) to offload spinal compression

Once you feel correct lumbar support, you tend to recognize it immediately in any chair.

The mystery of “ergonomic lumbar support” disappears—it’s simply basic biomechanical physics applied consistently.

Learn more: Lumbar Support Biomechanics for Gaming and Office Chair Users

Types of Neutral Computing Styles

Neutral posture isn’t a single sitting position. Any posture that preserves healthy standing spinal angles—a balanced neck and a natural lower-back curve—qualifies as neutral, whether upright or deeply reclined. Summary of types:

-

Active vs Passive Neutral Posture:

the core distinction between muscle-driven and chair-supported neutrality. -

Active Neutral in an Ergonomic Chair:

how upright, muscle-supported neutral sitting is achieved across different chairs. -

Passive Neutral Posture Workstations:

reclined seating, open hip angles, and reduced spinal loading. -

Zero-Gravity Recline:

fully passive neutral postures inspired by NASA’s Neutral Body Posture. -

Neutral Mobile Computing Benchmarks:

best- and worst-case posture targets for phones, tablets, and multi-device work.

Active vs Passive Neutral Posture

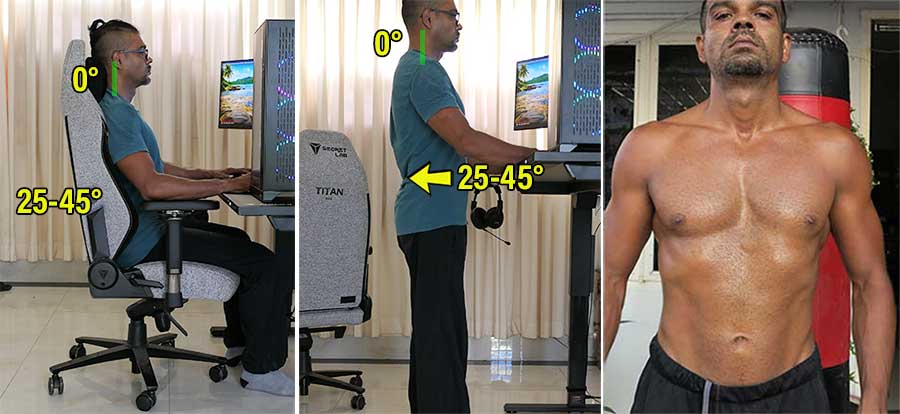

Jordan Tsai, a Doctor of Physical Therapy and member of Secretlab’s ergonomics advisory board, demonstrates an important distinction in neutral sitting: active versus passive neutral postures. In the image below, he illustrates both postures using a Titan Evo chair.

Both styles target the same biomechanics: a straight/neutral neck and a supported lumbar lordosis. The difference is where the work comes from:

- Active neutral posture: you hold the torso upright using your back and trunk muscles, using the chair mainly as light support.

- Passive neutral posture: you lean back into the backrest and lumbar support, letting the chair carry more of the torso load while maintaining the same neutral alignment.

In real use, the healthiest approach is usually switching between active and passive neutral throughout the day, rather than locking into one posture for hours.

Active Neutral in an Ergonomic Chair

Dr. Tsai once taught me—step by step—how to use a gaming chair headrest to support an active neutral posture with a zero-degree neck tilt.

That guidance helped refine my posture from a general “neutral” position toward the classic biomechanical benchmarks: a 0° neck tilt and a ~25–45° lumbar curve.

Subsequent testing in Herman Miller and Steelcase chairs reproduced the same alignment—this time using mid-back support and no headrest. This shows that the posture itself is chair-agnostic, provided the chair supports neutral biomechanics.

Across different chairs, these postures represent a generalized neutral ideal aimed toward established benchmarks.

Importantly, the goal is not to sit rigidly at these angles, but to use them as a baseline reference. Once users recognize their personal neutral alignment, they can move freely—and periodically return to that baseline to ensure posture remains intact.

Passive Neutral Posture Workstations

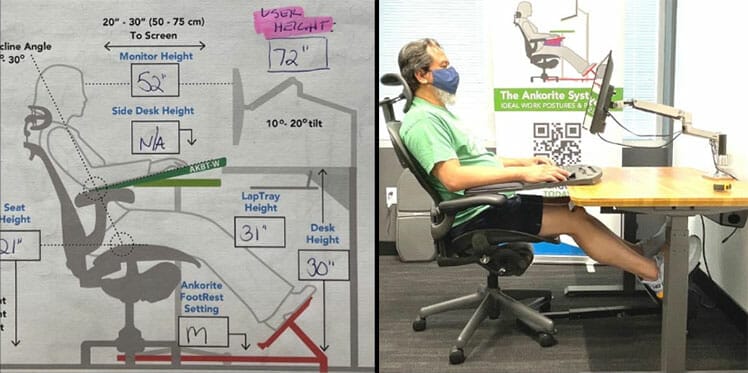

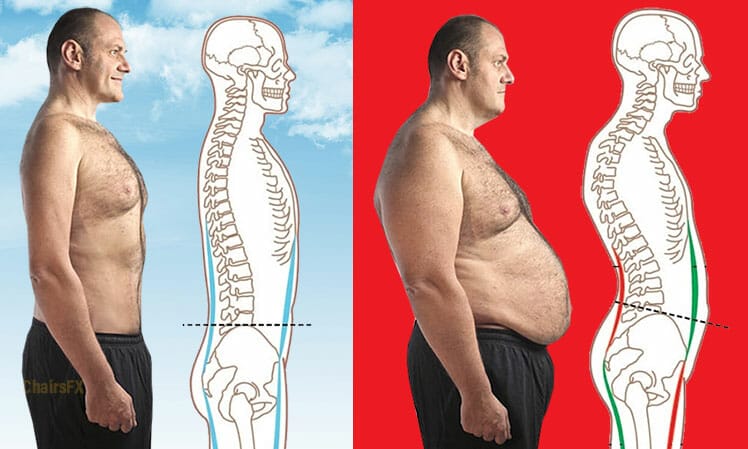

Biomechanical studies show that a moderate recline (~100°) combined with a wider knee angle reduces the total load absorbed by the seat and lower back(11).

In this configuration, body weight is distributed more evenly through the pelvis and spine, rather than being driven vertically downward by gravity.

This principle underpins a class of reclined neutral workstations designed to reduce spinal loading during prolonged seated tasks.

In 2023, ChairsFX spoke with Jeannie Koulizakis, founder of ErgoX and creator of the Ankorite System—a workstation concept combining chair, desk, and accessories to support reclined sitting with elevated feet.

Her work focuses on reducing spinal load through posture and workstation geometry. She has designed Ankorite-based workstations for organizations including NASA, the United States Department of Defense, and the United States Coast Guard(12).

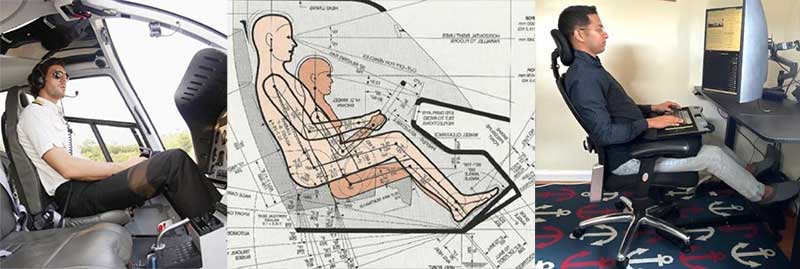

To explain the rationale, Koulizakis pointed to cockpit postures, where fatigue prevention is crucial. Healthy pilot seats uses lumbar support combined with recline to maintain a straight neck and preserve spinal curves, specifically to reduce sustained muscular effort.(13)

Zero Gravity Recline

The term “zero-gravity recline” is commercial and ergonomic shorthand for seating positions that approximate NASA’s NBP under gravity.

“Zero-gravity recline” is not a formally defined scientific term. Rather, it’s a descriptive label that conveys a fully passive posture. It generally implies:

- A reclined backrest (often ~100–130°)

- An open hip angle

- Leg elevation

With a zero-gravity recline, the backrest and lumbar support carry most of the torso load, instead of the user’s spinal muscles.

Conceptually, the intended benefit is load redistribution. Recline shifts body weight away from vertical spinal compression, while lumbar support maintains spinal curvature and leg elevation reduces pressure at the knees by transferring load into the seat and backrest.

When executed well, this configuration can reduce muscular effort and perceived spinal loading during prolonged sitting.

Neutral Mobile Computing Benchmarks

The 5th edition of the Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics(14) does not introduce fundamentally new biomechanics for desk-work sitting (e.g., new lumbar angles, new neutral posture definitions, or revised NBP principles).

Instead of redefining posture science, the handbook reaffirms long-established seating concepts while expanding focus toward human–technology interaction in modern, multi-device work environments.

Although the handbook does not specify precise biomechanical targets for mobile-device use, established benchmarks exist for both worst-case and best-case scenarios.

Negative Mobile Posture Benchmarks

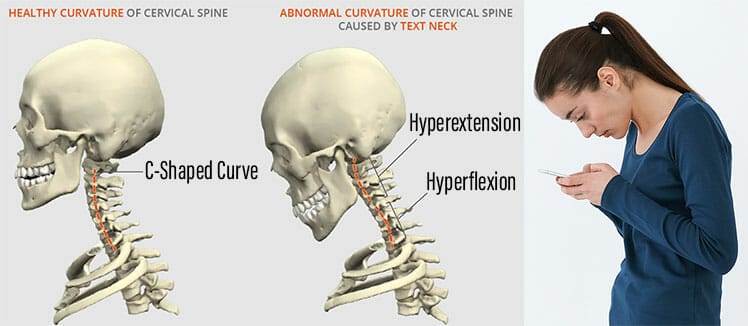

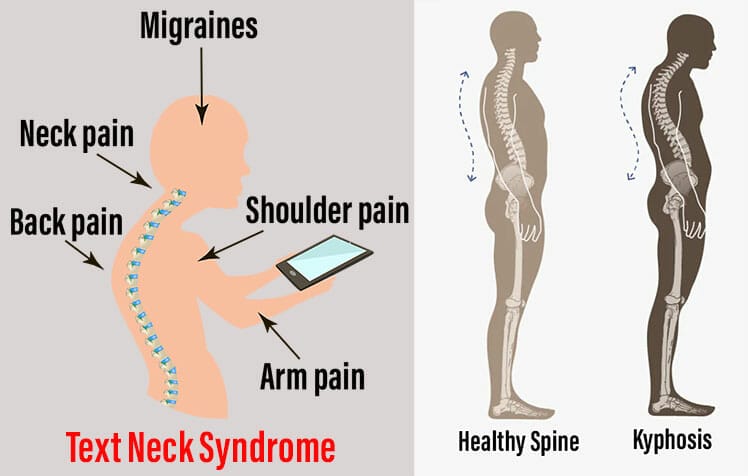

An adult human head weighs approximately 10–12 lb. As the neck flexes forward, effective cervical loading rises sharply.

In a neutral (0°) posture, cervical load is ~10–12 lb; at 15° flexion it increases to ~27 lb; and at 30° flexion to ~40 lb(5).

Sustained exposure to these loads places significant strain on cervical discs, ligaments, and surrounding musculature.

Over time, habitual forward-head posture contributes to excessive thoracic kyphosis and chronic neck–upper-back fatigue.

Learn more: Text Neck Syndrome Problems & Solutions

Positive Mobile Posture Benchmarks

A recent smartphone ergonomics study(4) tested a neutral ~0° neck position with varying elbow flexion angles (15°, 30°, 45°, and 60°).

Among the tested conditions, ~30° flexion produced the lowest combined muscle activation across key neck and shoulder muscles, plus the lowest discomfort ratings for both regions.

Although not a universal prescription, this provides a practical, biomechanically grounded benchmark for everyday mobile computing:

- Keep the neck neutral rather than bending it forward

- Bring the device up toward eye level, instead of lowering the head

- Allow a moderate elbow and shoulder bend (~30°) to support the arms

In daily use, I’ve found these broad targets highly actionable. Holding my phone higher with bent elbows noticeably reduces neck strain, even during short interactions.

The same principle translates to sit–stand desks: raising the desk into a “mobile mode” height allows the shoulders to remain moderately flexed while keeping the neck upright.

Neutral Sitting Limitations

When understanding ergonomic sitting science, context matters. Neutral sitting postures are an important foundation—but not a complete solution.

They provide a clean biomechanical baseline you can internalize, return to, and deliberately deviate from as tasks, fatigue, and focus change.

But in the broader picture of desk-work performance optimization, neutral sitting is a small but foundational piece of the puzzle:

-

Dynamic Postures Over Static Ones:

why even “perfect” posture becomes harmful when held too long. -

Standing Breaks Are Essential:

the strongest evidence-backed intervention for long-term back health. -

Good Posture Needs Core Strength:

why muscle capacity—not chair mechanics—determines posture durability. -

Healthy Habits Over Chair Picks:

why daily behavior predicts outcomes better than equipment choice. -

Physical vs Psychological Comfort Factors:

why biomechanics stay constant while perceived comfort and luxury vary by chair.

Big picture: neutral posture gives you a clean baseline—but movement, strength, and habits determine results . A good chair supports alignment between breaks; it does not replace breaks, conditioning, or lifestyle fundamentals.

Dynamic Postures Over Static Ones

Neutral postures align the spine and reduce muscular strain—making it easier to sit comfortably with good form. But there’s a hard limit: static sitting becomes harmful over time, even when the posture itself is “correct.”

Prolonged stillness creates postural fixity—a static loading pattern where some muscles (often neck, shoulders, lower back) are overworked while others are underused, and circulation drops(15).

That’s the real reason “dynamic sitting” became a design trend in high-end chairs. Tilt systems and flexible mechanisms try to encourage subtle motion and redistribute load. But the evidence doesn’t support fancy chair motion as a meaningful solution.

A 2013 systematic review(16) found no clear evidence that dynamic chair functions improve outcomes. Instead, it concluded that joint and muscle activity is influenced far more by what you do—standing, walking, stretching, task variation—than by chair mechanics.

The modern takeaway is simple:

- Use neutral posture as your baseline (spinal alignment, low strain).

- Break stillness frequently with small position shifts and posture changes.

- Rely on real movement—not chair gimmicks—for meaningful relief and long-session comfort.

This reframes “ergonomics” in practical terms: the goal isn’t perfect posture held for hours—it’s clean posture + constant variation.

Standing Breaks Are Essential

Once the limits of static sitting are understood, the most effective countermeasure becomes obvious: get out of the chair regularly. Standing and walking breaks interrupt static loading, restore circulation, and re-balance muscle activity in ways seated adjustments cannot.

Clinical evidence supports this directly. A 2024 Macquarie University study found that an education program combined with regular walking breaks was nearly twice as effective at preventing lower back pain recurrence compared with passive approaches such as rest or symptom management(17).

Importantly, the benefit came from movement itself, not from changes in sitting posture or equipment.

Broader clinical research reinforces the same pattern. A 2025 review in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine showed that most doctor-prescribed treatments for lower back pain provide only marginal benefit over placebo(18).

In contrast, movement-based and lifestyle interventions—walking, light exercise, posture variation—consistently outperform passive or device-based solutions.

From an ergonomic perspective, this reframes the role of the chair. A good chair helps you sit cleanly between breaks, but standing and walking breaks are what preserve long-term back health.

Good Posture Needs Core Strength

Neutral sitting postures reduce spinal strain by aligning the body efficiently—but they do not eliminate muscular demand.

Even in a well-configured ergonomic chair, maintaining an upright torso and neutral spine still requires sustained engagement from the core and back muscles.

This explains why posture often deteriorates over time, even in “perfect” setups. When postural muscles lack strength or endurance, the body defaults to slouching, leaning, or collapsing into passive positions.

No chair mechanism can fully compensate for weak or fatigued stabilizing muscles. Instead, several studies show superior outcomes from walking, Tai Chi, and holistic lifestyle interventions.

These all share a common mechanism: they improve muscular capacity and coordination. Stronger, better-conditioned muscles tolerate seated loads longer and recover faster between work sessions.

This is also reflected in performance-oriented fields. Esports professionals and elite chess players increasingly treat desk work like an athletic activity—prioritizing physical training, movement, and recovery alongside posture.

In this framework, the chair supports alignment—but muscle strength determines how long that alignment can be maintained comfortably.

Key takeaway: ergonomic chairs make good posture easier, but strength and endurance make it sustainable.

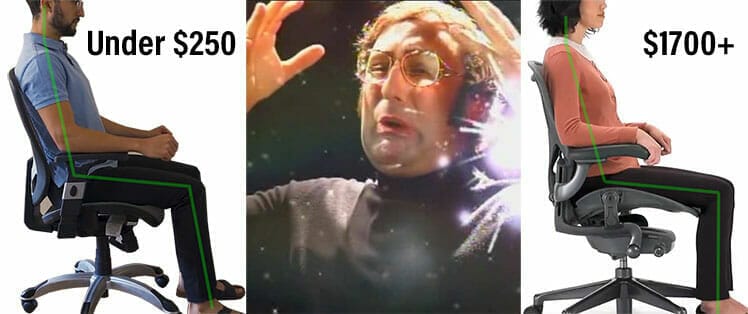

Healthy Habits Over Chair Picks

By this point, a clear hierarchy emerges. Ergonomic chairs help support clean alignment, but they play a minor role compared to daily habits.

Movement, physical conditioning, rest, and nutrition consistently show stronger links to reduced back pain, higher energy levels, and sustained desk-work performance than any specific chair feature.

This explains why some people thrive on basic seating while others struggle in high-end ergonomic chairs.

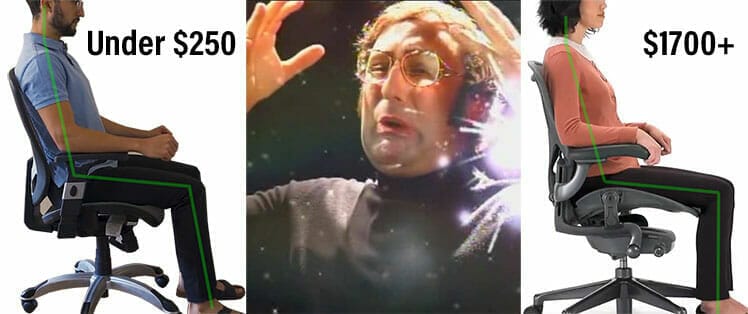

In a ChairsFX survey of desk workers reporting zero or minimal back pain, chair type showed no strong relationship to outcomes: pain-free respondents used a similar mix of ergonomic and non-ergonomic chairs.

In contrast, consistent differences emerged in daily habits—movement frequency, exercise, and overall lifestyle.

The implication is clear: chair choice alone does not predict desk-work health. Habits do.

Physical vs Psychological Comfort Factors

Research on automotive seats, aircraft seating, and office ergonomics consistently shows that comfort has two distinct components: a physical (biomechanical) one and a psychological (perceptual) one.

Physical comfort is defined as an “absence of discomfort”. It refers to the body’s response to posture support—specifically, whether a chair helps preserve neutral spinal alignment with minimal muscular strain. This is objective, measurable, and largely governed by biomechanics.

Psychological comfort refers to how a chair feels to the user: materials, softness, visual appeal, perceived luxury, feature richness, and brand associations. These factors influence satisfaction and preference—but they do not change the underlying postural mechanics.

Once neutral posture benchmarks are understood, an important pattern emerges:

Whether it’s a $150 task chair or a $1,900 flagship model, the biomechanical goal is the same: maintain a neutral neck and a supported lumbar curve using the same three controls—lumbar support, armrests, and recline.

What buyers usually compare are the execution details:

- Materials and upholstery feel

- Seat firmness and contouring

- Headrest, footrest, and deep-recline appeal

- Adjustment range and ease of use

- Build quality, warranty length, and brand experience

In short:

- Physical comfort = objective, posture-driven support

- Psychological comfort = subjective preferences and perceived luxury

Both matter—but they solve different problems. Confusing the two is what makes ergonomics feel vague. Separating them is what makes it understandable.

Conclusion: Ergonomics, Simplified

“Ergonomics” is often treated like a vague, subjective idea—comfort, preference, marketing, and endless feature debates. In reality, the core is straightforward.

The problem is that there’s no single authority that defines it, so the relevant facts are scattered across research, standards, and industry guidance. This article puts those pieces together into one simplified framework.

Ergonomic Seating Simplified

Chairs qualify as ergonomic when they give you the tools to maintain that baseline across tasks—namely adjustable lumbar support, adjustable armrests, and a reclining backrest.

Together, those three features make neutral sitting repeatable rather than accidental.

Once you understand the gist of neutral biomechanics—and the role of psychological comfort—chair shopping becomes simple. The neutral posture benchmarks don’t change from chair to chair. What changes is everything layered on top of them.

From there, the decision is no longer “which chair is most ergonomic,” but which category fits your body, budget, and preferences—then letting execution details make the final call. If you want help choosing within that framework, start here:

- Best premium ergonomic office chairs ($1,100–$1,900): crisp neutral support, top-tier build quality, and long warranties (often 12 years).

- Best premium gaming chairs ($400–$700): flexible neutral support with more comfort-forward extras and typically ~5-year warranties.

- Best ergonomic office chairs under $300: budget models that can still hit neutral posture benchmarks with the right setup.

Final takeaway

The biggest takeaway is the one modern evidence keeps pointing to: neutral posture is foundational—not a silver bullet.

If you want long-term back health and high performance at a computer, use neutral sitting as your baseline inside a larger system—frequent walking breaks, regular exercise/strength work, and solid recovery habits like sleep and nutrition.

Footnotes

- NASA, ‘Man-Systems Integration Standards (NASA-STD-3001), Volume 1: Crew Health’. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Section: Neutral Body Posture (NBP), https://standards.nasa.gov/standard/NASA/NASA-STD-3001_VOL_1, (accessed 4 Jan. 2026).

- R M Lin, I M Jou, C Y Yu, ‘Lumbar lordosis: normal adults’. J Formos Med Assoc. 91(3):329–33, 1992, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1354697/, (accessed 4 Jan. 2026).

- Jennifer Pynt, Martin G Mackey, ‘Seeking the Optimal Posture of the Seated Lumbar Spine’. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 17:5, 2001, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224029048_Seeking_the_Optimal_Posture_of_the_Seated_Lumbar_Spine, (accessed 4 Jan. 2026).

- Suwalee Namwongsa, et al. ‘Effect of neck flexion angles on neck muscle activity among smartphone users with and without neck pain’, Ergonomics. 2019 Dec;62(12):1524-1533. DOI: 10.1080/00140139.2019.1661525, (accessed 4 Jan. 2026).

- Kenneth K. Hansraj, ‘Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head’. Surgical Technology International, Vol. 25, 2014, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25393825/, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026).

- Étienne Grandjean, ‘Fitting the Task to the Man: An Ergonomic Approach’. Taylor & Francis; 3rd ed., 1980, https://www.abebooks.com/9780850661927/Fitting-Task-Man-Ergonomic-Approach-0850661927/plp, (accessed 4 Jan. 2026).

- Bill Stumpf, ‘Bill Stumpf (Industrial Designer)’. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Stumpf, (accessed 4 Jan. 2026).

- Gavriel Salvendy & Waldemar Karwowski (Eds.), Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 1st ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2005,

https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Handbook+of+Human+Factors+and+Ergonomics%2C+5th+Edition-p-9781119636090, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026). - ANSI/BIFMA G1-2013, ‘Ergonomics Guideline for Furniture Used in Office Work Spaces Designed for Computer Use’, BIFMA International, https://www.gmbinder.com/share/-OIcYOBmCNuDyAwDpL0U, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026).

- OSHA. ‘Computer Workstation Components: Chairs’. https://www.osha.gov/etools/computer-workstations/components/chairs, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026).

- Sang-Hwan Park, Jung-Hyun Kim, & Sung-Ho Kim, ‘Effects of Seat Back Angle and Knee Angle on Whole-Body Vibration Exposure’, Applied Ergonomics, Vol. 41, No. 6, 2010, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022460X10000684

, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026). - ErgoX.com. “Computer Workspace Design”. https://www.ergorx.com/, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026).

- Pro Aviation Tips. ‘Correct Pilot Seating Position: Why Is It So Important?’. January 22, 2023. https://proaviationtips.com/pilot-seating/, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026).

- Gavriel Salvendy & Waldemar Karwowski (Eds.), Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 5th ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2021, https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Handbook+of+Human+Factors+and+Ergonomics%2C+5th+Edition-p-9781119636083, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026).

- Nico J. Delleman, et al., ‘Working Postures and Movements’. CRC Press, 2004, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.1201/9781482265095/working-postures-movements-christine-haslegrave-nico-delleman-chaffin, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026).

- Jennifer Pynt, ‘Rethinking design parameters in the search for optimal dynamic seating’. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 19(2), 2015, DOI: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2014.07.001, (accessed 5 Jan. 2026).

- Professor Mark Hancock. ‘Walking to combat back pain: world-first study shows dramatic improvement’. The Lighthouse, June 2024. https://lighthouse.mq.edu.au/article/june-2024/walking-away-from-pain-world-first-study-shows-dramatic-improvement-in-lower-back-trouble, (accessed 14 Sept. 2025).

- Aidan G Cashin, et al. ‘Analgesic effects of non-surgical and non-interventional treatments for low back pain’. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, March 18, 2025. https://ebm.bmj.com/content/30/4/222.info, (accessed 14 Sept. 2025).